In our work at The Max Foundation, we treat every person facing cancer not just as a patient, but as an individual who belongs to a family and a community. Access to treatment is one of many barriers that patients face throughout their cancer journey.

We asked our partner hematologist in Malaysia, Dr. Ong Tee Chuan, to share his experience helping patients navigate their cancer journey and shed light on the various implications of treatment access. Dr. Ong has been practicing hematology for over 20 years, and is a clinician at Hospital Ampang in Selangor.

How do you explain access to treatment?

Dr. Ong: Access to cancer treatment— and to any medical intervention as a whole, be it health care, diagnostic testing, or treatment modalities—has significant clinical impact in patients’ outcome.

Once a treatment strategy has been proven to have high clinical value, it is important to ensure the universal availability of the treatment to all patients who need it. Universal availability does not mean free for everyone, but [[treatment]] should be available according to a cost that is affordable to the needed population.

In this case, much is relied on the healthcare financing and delivery system of each community, which is obviously an extremely complicated issue.

Based on your experience treating many patients, what are some of the barriers that patients and families face with access to treatment?

Dr. Ong: Access to treatment starts from access to health care, which in the ideal world must be simple, hassle-free, close to home, and affordable. The most obvious hurdle is the cost.

However, in the real world, even if the needed medication can be supplied at an affordable cost (or even free), there are still many logistical issues to look at. Constraints on the patient’s socio-economic condition can hinder access to treatment.

We have to realize that healthcare delivery is extremely complicated and intertwined with every aspect: politics and policy, economy, societal values and beliefs … just to name a few. Treating a disease might be a biomedical model, but managing a patient must go beyond biomedical thinking.

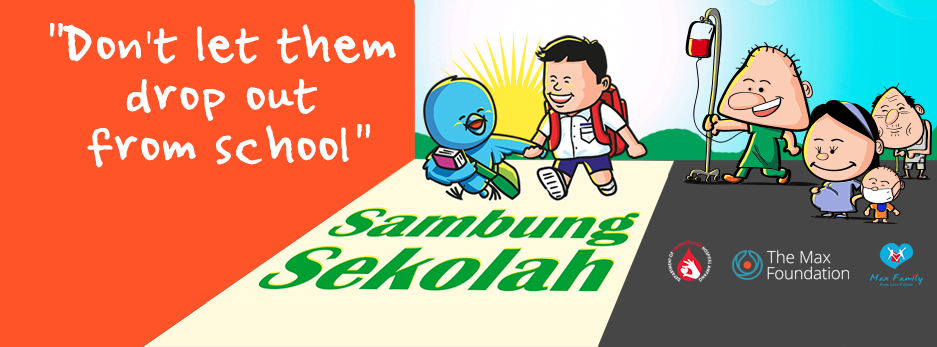

In 2014, you initiated a project helping children of cancer patients continue schooling while their parents were undergoing treatment. Can you tell us about The Max Schooling Project (Projek Sambung Sekolah) and how this project developed?

Dr. Ong: There are many hidden reasons why some patients cannot follow a treatment plan. For highly curable cancers, compliance to a treatment plan is one of the most important factors to cure the disease and to restore health.

Many patients earn daily or weekly wages, and many don’t have an adequate safety net for getting full wages while on prolonged medical leave from work. We have seen families struggle economically when the bread winner must stop working due to illness and the demanding schedule for treatment.

Children of patients are the unseen victims of disease; some might stop going to school for economic reasons or social reasons (no one can send them to and pick them up from school).

We believe that patients should not suffer from social-economic hardships when they have a catastrophic illness. The Max Schooling Project aims to give assistance to the children of patients, to help maximize their chance to complete at least secondary education.

Have you seen a change in treatment outcome for parents with children part of The Max Schooling Project?

Dr. Ong: The main aim of The Max Schooling Project is trying to ensure the affected child can have a life like their other peers.

They can join an outing organized by the school (when fees are needed), the family can have a meal in a restaurant when a milestone of treatment is achieved, or the kids can buy some extra materials during school activities.

Treating a disease must not be the top priority, it is how we treat each patient as an individual, a unique individual. Many kids benefit from the support, and we believe there is significant and sustained ripple effects from preventing [cancer patients’] children from dropping out from schools.

Dr. Ong recently published a book, Tales of Medicine and Mankind, about health care policy, treatment access, and delivery. Part of the book sales are going toward The Max Schooling Project. Read The Max Schooling Project 2020 Report to learn more.